Arizona Trail Q&A

What is the Arizona Trail?

The Arizona Trail is an 800-mile National Scenic Trail through the state of Arizona, running from the border with Mexico up to the Utah state line.

Whose ancestral lands was the trail built on?

From the Arizona Trail Association:

Arizona has been inhabited by Indigenous people for over 10,000 years. Today, the Grand Canyon State is home to the Ak-Chin Indian Community (Ak-Chin O’odham); Cocopah Indian Tribe (Kwapa); Colorado River Indian Tribes (Mohave, Chemehuevi, Hopi and Navajo); Fort McDowell Yavapai Nation (Abaaja); Fort Mojave Tribe (Pipa Aha Macav); Gila River Indian Community (Akimel O’odham); Havasupai Tribe (Havasuw `Baaja); Hopi Tribe (Hopi); Hualapai Tribe (Hualapai); Kaibab-Paiute Tribe (Kai’vi’vits); Navajo Nation (Diné); Pascua Yaqui Tribe (Yoeme); Pueblo of Zuni (A:shiwi); Quechan Tribe (Quechan); Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community (Onk Akimel O’odham and Xalychidom Piipaash); San Carlos Apache Tribe (Ndé); San Juan Southern Paiute Tribe (Kwaiantikowkets); Tohono O’odham Nation (Tohono O’odham); Tonto Apache Tribe (Te-go-suk); White Mountain Apache Tribe (N’dee); Yavapai-Apache Nation (Wipuhk’a’bah and Dil’zhe’e); and Yavapai-Prescott Indian Tribe (Wipuhk’a’bah).

We acknowledge that every foot of the Arizona National Scenic Trail is on the ancestral lands of Indigenous people, and are grateful for the opportunity to be stewards of the trail that traverses and connects these lands.

How long does it take to thru-hike?

This obviously depends on your pace, but 6-8 weeks is a common estimate. It took me two months to finish, going about 14 miles per day (here was my daily mileage). You can also hike the trail in sections over a longer period of time!

Why did you decide to thru-hike the Arizona Trail? Had you done something like this before?

This was my first thru-hike, but I’ve always loved to walk. In 2014 I walked the 500-mile Camino de Santiago across Spain, sleeping in hostels each night.

Flash forward. In 2017, I moved to Arizona to work on a conservation corps (ACE) via AmeriCorps. This was my first time camping. We worked outside for 8 days at a time, 10-hour workdays, tents every night. I quickly fell in love with the outdoors, got comfortable camping in a variety of Arizona’s landscapes (including 1.5 months at the Grand Canyon), and actually worked on a few different parts of the Arizona Trail, too.

The following summer and fall (2018) I was an assistant crew leader with Rocky Mountain Youth Corps (also via AmeriCorps). During this time I got used to working at altitude (on Mt. Evans), gained more experience with bears/bear safety, and used a water filter for the first time. In the fall, one of my crew’s projects involved hiking 250 miles of the Continental Divide Trail (CDT, another National Scenic Trail) and taking down trail data. This definitely boosted my confidence, feeding the belief that I could thru-hike the Arizona Trail. Also, during both seasons I worked side by side a very experienced thru-hiker (who thru-hiked the AZT in 2012), so learning of his experiences planted the seed and also made the feat seem more doable.

I loved Arizona’s climate and landscapes, I love to hike, I love to spend time alone, and I love a challenge, so thru-hiking the Arizona Trail seemed like something I would very likely enjoy. (I did!) I knew the best time to hike it would be spring, with the snow melt providing nice water sources, so in my mind I decided spring 2019 I would thru-hike the AZT.

What sort of preparation did you do?

In December, 2018 I started buying ultralight gear, as it was something I wanted to own and use beyond the AZT. I spent January and February visiting a friend in France—and during that time I bought a train ticket to Arizona for early March. I kind of tried to start plotting out possible daily mileage, but didn’t get far.

Near the end of that stay in February, I received news that my close friend in Wisconsin had passed away. Thus when I returned to snowy Wisconsin and had a single week before my train ride to Arizona—a single week to estimate mileage, grocery shop, make all of my resupply boxes, pack, etc.—I was consumed by grief. It was intense, but somehow I got myself to the southern terminus, and I began walking north.

So, I did zero physical prep. The first time I wore my full pack—with 4L of water and food—was on my walk to the Greyhound station for my bus to Tucson. I knew my body would adjust, and it did. You do what’s best for you!

What was trail density like? How often did you run into other thru-hikers?

The first day of my hike, I was a bit worried that I’d be running into people more frequently than I’d wanted—as I like my solitude. I counted at least 12 other people who began the same day I did. Nobo in spring is definitely the most popular route for the AZT. As time went on, though, I lost and hit bubbles of hikers—because of my pacing and theirs. On average I would usually see at least two other thru-hikers/bikers in a day, sometimes more (but spaced out), though by the last third of the hike I had chunks of days where I didn’t see any other thru-hikers.

On days when I kept running into the same person, leapfrogging, it was because we had very similar pacing. I generally didn’t take zeros, and I think that played into me not falling into a bubble of same-paced hikers. (Also, most thru-hikers were faster than me, so usually I was getting passed… until they were all in front of me!) I feel start date, weather, and pace are still the largest factors in what the trail traffic will look like.

Certain areas of the trail have higher day-hike usage than others, so in some places—especially on weekends—expect to run into day hikers. I don’t keep up with thru-hiking culture, but apparently a well-known filmmaker/thru-hiker Darwin made a film this spring (2019) while thru-hiking the AZT—so I suspect that will make numbers jump in the coming years.

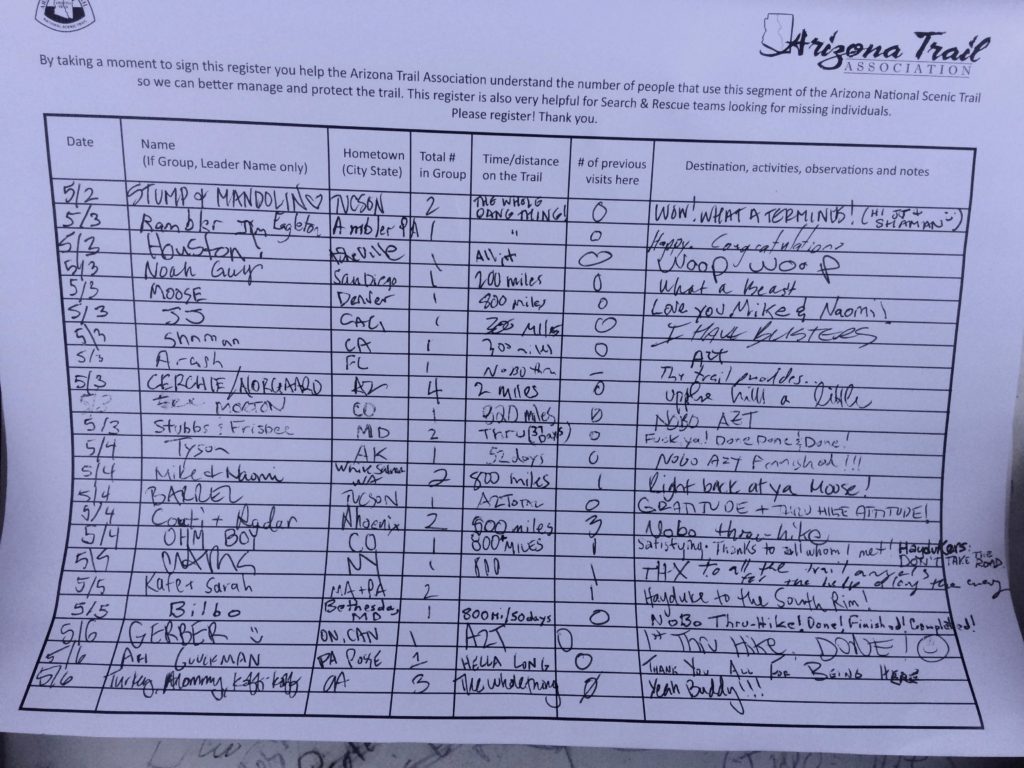

The AZT Association compiles data each year from their trail finishers survey and trail logs—I think they’ll update in Jan/Feb 2020 with 2019 data. In glancing at the trail logs I took pictures of at the northern terminus, though, it looks like about 1-5 entries per day were from thru-hike finishers in May, so that kind of gives an estimate.

What did you do for maps?

I bought official maps for $45 from the Arizona Trail Association (ATA) to have a paper copy with me. I split them up in some resupply boxes so that I wasn’t leaving with the full stack. I mailed these home once I’d finished big chunks, again to not carry so much paper weight. I brought a compass along, too, but never had to use it.

I used the Guthook app as well, and purchased their Arizona Trail guide ($9.99). It has the full trail mapped out, plus water sources, town stops, points of interest, etc. Super handy, definitely recommend if you use a smartphone. The app uses your phone’s GPS to show you where you are at any point along the trail, and tells how many miles until future waypoints (ie next water supply). It works in airplane mode.

Did you get lost? Is the trail well marked?

No, I didn’t get lost, and the trail is well marked. There were two instances where I walked on the wrong trail for a mile or two, but I soon realized my error and turned around.

How was phone service?

I kept my phone in airplane mode 98% of the time, and turned it off at night. My provider is Cricket Wireless. My first notably long stretch without service was maybe six days, which included the town of Summerhaven.

Then after leaving Flagstaff, I had no service for over a week (almost two), since I don’t get service at the Grand Canyon. (Mather Campground in the Canyon has wifi, so I was able to send an iMessage saying I was all right, etc.) And finally, I didn’t have any service in Page, AZ! All phone providers have different coverage, but I would simply plan to not rely on it.

How did you charge your phone?

I had a solar charger (Goal Zero Nomad 7) that I already owned, so I brought it along.

How did you get to the southern terminus?

I took a Greyhound bus to Tucson (from Flagstaff, where I arrived from the midwest via Amtrak train), and arranged to have a trail angel drive me to the southern terminus (as close as you can get—you can’t drive to the actual start). Here’s ATA’s information about getting to the southern terminus. There are shuttle companies that give rides as well, here is their information.

Where do you go when you finish the trail?

The northern terminus is at Stateline Campground, a free BLM campground on the UT/AZ state line (first come, first serve, 14-day max stay). There are pit toilets, but no water source. (I filled up my water when I had just a few miles left of the trail, so I would have enough overnight.) The campsites each have their own pavilion, so I cowboy camped (it rained, the roof over my head kept me dry, it was awesome) and then got a ride the next morning to Page, AZ.

Most people go to either Page, AZ or Kanab, UT when they finish at the northern terminus. I would first try to find a ride from someone at the campground. (I was able to find someone right away who was heading into Page the next morning—hooray!) People are kind, and especially so when they find out you’ve walked there from Mexico!

If you’re unable to find a ride at the campground, walk 1.5 miles north (take a left leaving the campground) on House Rock Valley Rd to Wire Pass Trailhead. The parking lot was very full when we drove past on our way to Page, so that’s another great option for finding a ride to Page, AZ or to Kanab, UT. If you know your exact finish date, you could also reach out to a trail angel to plan for a ride.

What is the weather like?

There will be snow, hot desert, forest, and more snow. As you gain elevation, temperatures will be cooler. I had two or so days of rain (with cold hail!), and many sunny days. The people who started a week earlier than me had tons of snow, so watch the weather and ATA’s latest trail news on their homepage.

I started on March 14, and hiked through (and slept on) snow that first day, on Miller Peak. (Like I said above, elevation is a huge factor when it comes to temperatures. Also: how far south/north you are in the state.) I finished the hike mid-May, and was surprised to wake up to snow my second-to-last day on trail!

For sun: Bring sunscreen and sun protection. I wore two bandanas (to protect ears/neck/chest), a hat, a long sleeve (thin, breathable!) button up, and gloves (to protect hands) every day—plus sunscreen—for sun protection.

Here’s another trick you can use: Soak a bandana in cold water, inside a ziplock (might want to double zippie that) and keep it at the bottom of your backpack. Then, in the middle of the day when you’re feeling the heat, pull it out and put it around your neck. The back of your neck is where your body takes temperature readings, so it’ll really cool you down to put something cold there. The Grand Canyon is a great place to use this trick—it was 92 at the bottom when I crossed in April. Take breaks in the shade! Stay hydrated and eat your salty snacks!

For cold: I had a hat, a warm buff (around the neck), a puffy jacket (Patagonia), another long sleeve layer, and gloves for the cold. I was so thankful for my Dirty Girl Gaiters that first day when I was trekking through waist-high snow on Miller Peak. Had there been any more snow/rain/hail than what I encountered, it would have been very useful (and warm) to have a water-proof glove/hand covering and a shoe covering. Luckily my cold rainy days were always followed by a sunny day, so I could dry out and warm up. And I was always warm at night in my 22-degree (F) bag (with 15-degree liner). Don’t forget to sleep with your water filter on cold nights!

Do you need camping permits anywhere along the trail?

You will need a backcountry permit to sleep in Saguaro National Park and in Grand Canyon National Park. In Saguaro, the permit is $8, and I called and purchased it over the phone the day before I arrived. There are three sites at Grass Shack Campground (in Saguaro)—but they’re enormous! There’s a huge bear box for each site, plus a pit toilet. I’d felt lucky when I called and was given the last spot, but upon arrival I realized it wouldn’t have been a big deal if they had been “full.” I let other thru-hikers camp on my site, and I still had a lovely private nook all to myself. Each site has ample space for many tents. So, when you’re getting close, call and try to make a reservation. If they’re completely full, hope that the folks who have reserved are fellow thru-hikers or kind people who won’t mind you sleeping the night. Again, it’s spacious and I wouldn’t see this being a problem.

At the Grand Canyon, I went to the backcountry office and they helped me get my permits for the following night. It’s a $10 fee, plus $8/night. I got two nights, because I didn’t think I’d make it out of the park on the north rim on the second day (I didn’t), so the permit allowed me to dispersed camp within the park limits.

What’s a trail log/registry?

Many trailheads will have a registry where you write your name, date, and any comments as you pass through. It’s fun to see where other thru-hikers are, as well as passing words of encouragement to one another. (It’s also a great place to thank Arizona Trail Association and other public lands workers/volunteers!) But the registry is also used in case of search and rescue. So, if signing with a trail name, make sure someone back home knows what name you’re going by on trail.

Did you cook on trail?

Yes! I used a pocket rocket stove and 8oz IsoPro fuel. I really loved having a warm meal in the evenings.

Fuel: I used three 8-oz fuels for the full hike, so each lasted around 20 days. I didn’t finish any completely; but I switched to a new one when I picked up my resupply box and left the other behind in a hiker box. When you get to the Grand Canyon, if you camp at Mather Campground, there was an overflow of partial fuels, because many tourists use them but can’t fly home with them… so they dropped them off at the hiker/biker campsite. I made lots of tea while I was camped there!

What did you eat? How did you resupply your food while hiking?

Here’s what I ate as a vegan on trail. And here’s everything you could ever want to know about my resupply boxes.

What about water?

I used a Sawyer Squeeze on my thru-hike to filter water, and had AquaMira as well (drops used to treat water).

AquaMira: Don’t buy the 2oz bottles like I did. I found out on trail at an inopportune moment that there’s no dropper, just a pour spout on those bottles!

Water filters: Don’t forget to sleep with your water filter when it’s below freezing. I honestly recommend getting in the habit of sleeping with it every night, just so you won’t forget. You change elevation a lot, so you’ll go from snow to desert to snow again.

Sawyer Squeeze: The filter itself worked great, but the bags are terrible! Even the “thicker” bags all got holes in the same spot after a few weeks. And their flimsy bags only lasted a few days. (!) I contacted the company and asked what they were doing to make their product more sustainable (instead of just sending free replacement bags that are going to end up in a landfill after a few squeezes), and never got an answer to the question—just a replacement bag after I’d already purchased two full kits. (Long story.) So, I’d rather recommend a company and product that works well, and which is committed to sustainability. (Any recs?)

Water sources: I had great luck in the timing and year of my hike, in that water was plentiful in streams and creeks. Maybe 70% of the hike I refilled from natural sources, and 30% from cattle tanks?

It would be helpful to have a “dirty” cup (paper coffee cup would be perfect) to use for scooping water into the filter bags. I developed my own techniques over time, but at some of the algae-ponds with no flow it was difficult (took a long time) to fill my filter bag.

What was your water capacity?

I had two 1L Smart Water bottles (which fit on the outside of my pack straps), two 1L Gatorade bottles (side pockets of pack), and the Sawyer Squeeze bags. For a while I also had a smaller bottle I was mixing protein powder in, seen next to the Gatorade bottle below. But generally, “full” capacity in my mind was carrying 4L in the four bottles, though I could have carried 6L for longer stretches if need be.

If anything, I usually carried too much water. I carried an “emergency” 2L for the first few days, before I lowered it to an “emergency” 1L in my pack… which I may or may not have carried for 43 days before I trusted it was not necessary. (!) It took a while before I got used to filtering more frequently instead of carrying a full day’s water at a time.

When working on the conservation corps I would bring about 5-6L with me each work day, and sometimes finish it all, so I had a good gauge of what my body needs in these various climates.

What gear do you recommend?

Use what you have! Use what you like! Here’s what I packed.

Did you have a SPOT device?

No, I did not have a SPOT device. We had them with our RMYC crews, so I’m familiar with the benefit when in backcountry situations. I chose not to buy one for this hike based on my previous experiences in Arizona, my backcountry experience, my hiking style, Wilderness First Aid knowledge, and budget. That was right for me.

If you would feel at ease with one, by all means, get one! Listen to yourself.

Talk with your people about a safety plan before you leave. Should they expect to hear from you while you’re on trail? How frequently? What does your phone coverage map look like in Arizona? Etc.

What was your first aid kit like?

It was very minimal… it included a handful of bandaids and some moleskin I already owned. From a hiker box in Summerhaven I added a wipe for insect bites.

Luckily, I only ended up using one bandaid (well, two—but one I used to patch a tent hole!). Do what’s right for you!

Did you keep a trail journal?

Yes, I kept a journal with paper and pen while hiking! I may turn it into a zine in the future, but in the meantime, below are some online trail journals to get you started. I generally don’t like reading others’ experiences before I’m going to do the same thing, so I’ve only read Nathan and Nicole’s journals. You do you!

- Another Long Walk: Nobo 2014

- City Girl Gone Wild (Tink – aka Nicole Antoinette): Sobo 2017

- Free Roaming Hiker (Mike Cavaroc): Nobo 2016

- Hiking Dude: Nobo 2012

- Kevin Hikes (Junco): Nobo 2019

- Long Walks and Dirty Socks (Rainer – aka Nathan Ventura): Nobo 2013

- Roaming with the Romers: Sobo 2018

- Trail Journals (Various)

Finally, here’s the ATA list of trail finishers. If a name has a link, that means they have online resources about their hike (i.e. a blog/site/video), so that can be a good place to learn of others’ experiences.

Thank you for these resources! Can I pay you for the time/energy you put into these creations?

Absolutely! Thanks for asking. If you found this resource helpful, see its value, or have benefited from the energy shared, I invite you to make it a feel-good exchange between you and me. Here’s where you can pay what feels right on Paypal (or use the button below), or I’m @RebeccaThering on Venmo (-1437).

I happily accept zines and other trades, too! Money is energy. The energy I put into this involved a two month thru-hike plus two months of writing and documenting. Thanks so much for your attention and for being part of this energy swap. 🙂

Thru-Hiking Terms 101

cat hole – You’ll dig a cat hole (6-8 inches deep!) to poop in.

cowboy camp – This means to camp without setting up your tent—simply lying on your sleeping pad, staring up at the stars. (The desert is the perfect place to cowboy!)

LNT – Leave No Trace, a set of seven principles to help protect the natural world. (See this LNT 101 post.)

hiker box – A hiker box (pictured below) is a place to leave behind extra food/gear for other hikers, or where trail angels might drop off water. It has a locking element to keep animals out.

nobo – North Bound(er), hiking the trail from Mexico to Utah.

sobo – South Bound(er), hiking the trail from Utah to Mexico.

section hiker – A section hiker is hiking a long trail in chunks—perhaps a weekend here, a weekend there… a two-week backpacking trip every summer over years and years… So many ways to enjoy and experience this trail!

thru-hiker – A thru-hiker is hiking a long trail in one go—perhaps for a solid month, two months, or more, depending on the length of the trail.

trail angels – Trail angels are magical people who help hikers. They may offer their homes as places to stay or wash up, they may offer rides to/from trialheads and towns, they may drop off water and fruit in trail boxes… many forms! Here’s a helpful list of AZT trail angels.

trail magic – When beautiful trail angels leave treats for hikers!

trail name – Most thru-hikers go by a trail name, usually given to them by others. I don’t have a trail name yet! But to give you a taste, some of the people I met on my thru-hike were Puns, Jeronimo, Twiggs, Gummy Bear, Stitches, Junco, Nobo Lobo, Detour, Tour Guide, and Lorax.

trailhead – The start of a trail is a trailhead, and usually has a marker indicating such. Most larger trailheads have parking.

widow maker – A “widow maker” is any dead branch or tree that could fall and potentially hit you… in turn, making a widow, which is where the grim name of the term comes from. Look up and check for these before setting up your tent.

wilderness – When natural areas are designated as “Wilderness” by the U.S. Government, it means they’re restricted to foot or horseback travel (no bikes, no vehicles). Even trail workers can’t use chainsaws in Wilderness areas—only crosscut saws. As you would anywhere else, be prepared to respect LNT and regulations in these areas.

zero – A zero is a day where you walk zero miles of trail, usually taken in a town.

—-

Phew! After digesting this whole web of info, what questions do you have? Leave a comment and I’ll gladly answer!

Thanks so much for being here. I wish you a pleasant day!